Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research, Volume 9, Issue 2, pages 44–61.

Comic

Essi Varis

The Skeleton is Already Inside You:

A Metaphoric Comic on Speculation

Did you read the comic yet? If not, go read it now! It is about skeletons, so you will probably find it quite exciting! Then, you can come back here and read this accompaniment, if you like.

Alright, for those of you who have made it this far, I can now reveal that the comic is not really about skeletons at all. It is about speculation, which I have researched, primarily in the framework of cognitive literary studies, for the past couple of years.1 That probably sounds a little less exciting than skeletons, and the project is still ongoing, so I cannot say exactly how speculation works yet. However, I hope to have highlighted some of the reasons why we speculate and demonstrated that we often do so by engaging with texts and images, narratives, concepts, and metaphors.

Because our imaginative activities are so intertwined with imaginative texts and pictures, I did not want to write just another article; I wanted to publish something that would force both me and the readers to think about the mysteries of speculation in a more creative and unexpected way – in a way that encourages further speculation and interpretation. After all, one of my main motivations for researching speculation is my conviction that the creativity fueling artistic endeavors and the creativity required for innovative research are, at heart, the one and the same cognitive force. They are both intertwined with imagination and work through many of the same mental habits, like curiosity, flexibility, intuition, and reflection. However, they have to be aimed towards very different ends – such as Truth or Beauty2 – and pushed through very different socio-cultural moulds – such as peer-reviews or newspaper critiques. This ultimately produces very different end results.

I have often felt that both my artistic and academic outputs leave behind some unspoken, unseen, underutilised residue that would have been brought to the forefront if only the same ideas had gone through the other creative pipeline – if only I had been able to make art instead of doing research, and if only I had been able to do research instead of making art. It is precisely this residue that the present publication aims to salvage: the comic enacts my artistic, metaphoric understanding of my research topic, whereas this text you are reading now attempts to explain and analyse some of the conceptual and procedural insights gained from creating it. Each reader will likely need or appreciate one type of understanding more than the other, but as far as I know, presenting both together is also quite rare, and therefore, hopefully helpful or interesting to some.

Thinking through Comics, Metaphors, and Speculation

In short, this project aims to highlight three methods, modes or tools of thinking that are rarely used in academia with any overt or serious intent: comics, metaphors, and speculation. Admittedly, all three are at odds with the positivist ideals of science. Images and figurative language can appear vague and subjective compared to the precise, operationalised parlance of lab reports, and speculation is something that ventures beyond empiric evidence by definition. I would argue, however, that no great discoveries or innovations were ever achieved by precise and objective measurement of evidence alone; research and science also call for creative, flexible, lateral, and expansive thinking (cf. Leavy 5–16). As Patricia Leavy writes, “metaphor, symbolism, and imagination already guide qualitative ‘scientific’ practice, although within the shadows” (264). Perhaps this all too often neglected side of the inquiring mind could be engaged, fostered, and facilitated better with the kind of materials that definitive, linear, and logical lines of thinking reject – such as the visual, embodied, and playful affordances of comics, metaphors, and speculations?

Comics have already proven themselves quite effective in communicating both abstract concepts and empirical research findings. Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics (1993) is a classic in the field of comic studies in spite of being a comic, and the works of Joe Sacco have sketched compelling outlines for a new form of inquiry dubbed “comics journalism” (El Refaie). Yet, comics by researchers, comics for researchers, and comics as an integral part of the research process remain few and far in between. Some of the rare pioneers include Matteo Farinella, Uta Frith and Chris Frith, who explain central concepts of neuroscience in their comics, as well as Nick Sousanis, who managed to earn a doctorate in education with his comic-form dissertation, Unflattening (2015). Sousanis’ work explicitly presents the medium of comics as a powerful research and teaching tool that does not aim for closure in the manner of natural sciences, but promotes more open, imaginative understanding of the world and the human mind (71–97; cf. Leavy 12–15, 264–265). He also notes that excluding pictorial thinking and expression from academic contexts is a waste, because even if drawn images would not meet the positivist standards of precision or objectivity, they could be used in other ways, to widen, deepen, and perhaps even test the validity of language-based research writing (Sousanis 31–67). Moreover, as the Friths’ and Farinella’s works illustrate, drawn images have the power of communicating research findings in a way that is exceptionally concrete, immediate, and relatable.

The drawbacks of creating research comics are that the process is, of course, fairly time-consuming, and it requires skills that are typically not part of researchers’ professional training. So, thankfully, metaphorical thinking affords some of the same benefits as comics – it makes the abstract and the invisible more concrete, embodied, and memorable – and it is something the human mind does almost automatically. As per George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s classic theory, conceptual thinking is “fundamentally metaphorical by nature”: we understand the semantics of various concepts by mapping them on embodied experiences or by relating them to each other in virtual space (3). Similarly, Terence Cave maintains that metaphors are not “just” metaphors but an integral part of our cognitive ecology (142); they organise our behaviour and open new paths for thought and action (Lakoff and Johnson 7–9).

Traditionally, metaphors have been understood as vague semiotic signs, where the connotative vehicle simultaneously stands for and obscures the denoted tenor. While this is, perhaps, detrimental to the precision expected from positivist language, the mutable connections that metaphors suggest between concepts also leave space for speculation and exploration. That is to say, metaphoric association is an effective way of finding new, creative connections between various concepts across various domains, which in turn can lead to heightened understanding or innovation (Lakoff and Johnson 139–146). In this sense, metaphors do not necessarily obscure the denotative meaning, but rather, add to it in terms of depth and nuance, and even in terms of embodiment and movement (Cave 67–69). They are a concise linguistic strategy for inviting imaginative, associative “as if” thinking, “an economical short-cut to a virtual expansion” (ibid. 77), or a device that “unites imagination and reason” (Lakoff and Johnson 193).

In my experience, metaphors can be used to think through (narratological) theories in a surprisingly systematic manner (Varis Graphic Human Experiments). An apt, novel metaphor provides something of an alternative mould for the existing theory. This allows deconstructing the traditional way of thinking and testing its components against the new metaphor through rearrangement: what fits, what doesn’t, where the conceptual gaps and seams lie, and is there something everyone has overlooked so far? Of course, just like every theoretical approach, every metaphor makes some aspects and issues of the target theory more salient than others, but this partiality can be counteracted, for example, by employing several alternative metaphors, as I have done in this comic.

All in all, both comics and metaphors afford multimodal and embodied, associative and open-ended ways of thinking. Therefore, they might prove especially valuable for the investigation of such complex topics that traditional positivist methods have struggled to explain. Perhaps it is no coincidence that so many of the few pioneers of research comics have been neuroscientists, as the study of cognition has been undergoing a seismic paradigm shift. In the past few decades, more and more researchers across disciplinary boundaries have questioned the cognitivist idea of the mind as a symbol-crunching brain-machine and have, instead, started to view cognitive action as an embodied process that extends into various tools, environments, and creaturely relations (Varela et al.). Navigating this wider, interwoven landscape of consciousness requires radical redefinition of many cognitive processes, especially such complex activities as creativity, imagination, and speculation (ibid. 147–148).

As stated above, this comic focuses on the smallest of the three: speculation. It is by no means a popular research term (yet) – on the contrary, I have heard numerous colleagues to either apologise for speculating or even flat-out refuse to speculate. In many contexts, this is commendable; recognising and labelling speculation as speculation is important in the so-called post-truth era. Yet, for the same end, I believe it is helpful to define and investigate speculation further, rather than look away from it. Here, my working definition for speculation is: “a cognitive or artistic act of approaching or exploring an unknown or uncertain area or phenomenon in terms of possibility, through the playful or strategic use of imagination, as modified by one’s own perspective and the known circumstances”.3

As one might gather, this definition covers a rather large area of grounded, intentional imagining – the kind of imagining that creative research demands. This suggests that in some contexts, speculation could be embraced as a useful method, rather than rejected as an unscientific error. This is certainly how it is viewed among creative writers: fantasy and horror authors “simply” fabulate or make things up without explicit methodical limitations, whereas science fiction authors are considered to speculate or extrapolate – that is, to approach the realm of possible in a rational, systematic manner (see Varis “Kuinka kirjailija spekuloi?” in this issue). Thus, if metaphors can be considered “imaginative rationality”, as Lakoff and Johnson suggest (193), speculation could perhaps be dubbed rational imagination. Moreover, as the comic indicates, some limited forms of speculation – such as mind-reading or projecting the future – may be just as unavoidable as thinking through conceptual metaphors. Thus, if everyone is going to have to speculate either way, even scientists prioritising precision and objectivity might prefer to speculate openly and mindfully, rather than covertly or unwittingly.

Yet, the main benefit of speculation is the same as that of comics and metaphors: it creates openings, not closures. When used responsibly, it asks, guesses, and hypothesises, rather than claims, proves, or declares, thus reserving space for uncertainty, where new creative connections and discoveries can be born. This is, perhaps, where research and science often begin – but it is typically erased from the finished results and reports. Comics are the complete opposite of this kind of research writing, where every term is carefully defined, and every gap closed so tightly that all that remains is the certainty of new knowledge, and only an expert reader could possibly step in to question anything. Comics’ primary way of meaning-making, by contrast, is simply juxtaposing different elements: there is rarely an explicit “however”, “therefore” or “and” between two panels. Instead, it is ultimately the reader’s task to find the logic, cohesion, or “closure” (McCloud). In this sense, comics narration, much like metaphoric language, is ultimately an invitation to associate, compare and connect – to reside in the potentials of complex meaning (Lakoff and Johnson 192–194; Sousanis 61–63). Thus, one could say it is also close akin to speculation and its open exploration of possibilities within given parameters.

All this considered, it is quite clear that metaphoric comics will never replace analytic research writing as such; they will always be more ambiguous and more open to interpretation. However, these qualities should no longer be considered flaws that disqualify comics or metaphors as forms of academic communication. On the contrary, they could also be seen as strengths that have the potential of energising an entirely new kind of research writing – a kind of writing that does not aim to provide final, definitive answers for the reader but, rather, invites them to participate in the process of wondering, searching, and speculating. Alternatively, as the field of research comics expands, we could start dividing them into different genres, each with slightly different aims and advantages. Science and research could well benefit, for example, from schematic summaries resembling conference posters or infographics, from talking-head comics explaining established science (e.g. McCloud, Frith et al.), from comics and sketches documenting field research, as well as from comics produced in the process of exploring some abstract topic (e.g. Sousanis and this comic).

Yet, as long as academic comics remain a relatively unexplored frontier, making one is also an experiment in and of itself. So far, there are no guidebooks for approaching your research with the help of comics, so every attempt at something like this is very much a speculative cycle of trial and error. Crossing this uncertain sea can lead to failure – indeed, I find it quite impossible to assess whether the finished comic can give anything of value to anyone else – but it also fosters genuine creativity – which always entails some degree of learning and discovery. That is to say, even if the end product fails to engage its readership, the process has already given me some new insights into the topic of speculation and taught me many things about creative thought and the composition of comics. In order to share some of this understanding, I will next indulge in a bit of “shop talk” and explain how this first comic I have ever published came to be.4

Notes on the Creative Process

All five pages of this comic were created with Winsor & Newton watercolour, white Winsor & Newton drawing ink, Sakura Pigma Sensei markers, and Sakura Pigma Micron fineliners on Hahnemühle Bamboo Mixed Media paper (24 x 32 cm, 265 g/m2). Admittedly, watercolour is not a particularly popular medium for creating comics, because it does not provide very practical means of achieving the qualities that comics usually aim for: simplified, legible images that are speedy to create and easy to reproduce. On the contrary, the subtle tones and slightly unpredictable effects, which are the hallmarks of watercolour painting, are somewhat at odds with the clean linework that usually forms the backbone of a well-executed comic. However, as the skeleton remarks on page 5, this tension between the fluidity of watercolour and the preciseness of the fineliners is the main reason I chose this somewhat impractical technique.

Comics tend to be especially impactful and irreplaceable when their material or pictorial forms either reinforce or add new layers to their narrative meanings. Prominent examples of this include David Mazzucchelli’s graphic novel Asterios Polyp (2009), where the variance of colours and line qualities provides arguably stronger characterisation of the protagonists than the narration or the dialogue, and Mari Ahokoivu’s Oksi (2019), whose folk-artsy, highly simplified graphic style underlines the mythical quality of the creatures depicted in the story. While I do not claim this 5-page experiment to be on the same level artistically, the motivation behind its material genesis is the same. If speculation is a logical fantasy, a rational daydream, or an educated guess, what better way to meditate on it than by bringing together definite, unerasable lines and paints that unavoidably live a life of their own within and beyond those lines? Just like speculation, the ink and wash technique is a compromise between control and flexibility.

Page 4 is slightly different from all the other pages, because it is also a collage. That is, many of the elements “pinned” to the board are assorted pieces of scrap paper that I glued on the thicker mixed media stock. The assemblage also incorporates a quartered post-it note and a very low-resolution picture of George Orwell, which I cut from an 1984 issue of Image, University of Oslo’s English students’ culture zine. I found the issue laying around at a university copy room and wanted to make use of it because – again – this is exactly how creativity and imagination work. We gather bits and pieces, little morsels of material and inspiration wherever we go, and incorporate them – sometimes quite haphazardly – into whatever we happen to be creating at the time, or years and years further down the line.

All told, creating this comic took almost one semester – about four months – and looking at the entire process step-by-step, it becomes clear that my habitual artistic processes and research processes entered into a sort of dialogue where each took the lead in turn, usually when the other did not know how to continue. First, I started outlining the script the same way I would outline any research paper: by compiling a list of keywords and themes and looking for ways to group or connect them. Second came the sketching of the storyboards, which in turn resembled my regular drawing process. That is to say, I put logic and argumentation on hold and concentrated only on imagery and composition, laying out my chosen metaphors across four pages in a way that felt interesting or aesthetic. I also scribbled some initial notes for the textual elements straight between the sketches, without thinking about them too much. Third, I turned back to my researcher’s playbook again: I prepared cleaner versions of the storyboards and typed out a script, so that I could seek feedback from my colleagues.5 Their thoughts and reactions really helped me to reassess the script and its readability. Most importantly, I understood, on the one hand, that mixing several metaphors on one page confused the concepts behind them, but on the other hand, I also needed to add some recurring elements for the sake of cohesion.

As I often do in my processes of both academic and artistic creation, I let these thoughts rest – or indeed, compost – for some weeks in the back of my mind, until the vision for the revised storyboards started to emerge. I decided to leave the first and the final page – both of which featured a skeleton – more or less intact, but re-drew the pages in between them, so that each page would focus on one type of metaphor but also feature the skeleton in some shape or form. Separating the metaphors from each other like this required adding one more page, and the comic thus expanded from four to five pages in total.

For most of this revision stage, I was thinking almost entirely in pictures again, and inked and coloured each page as I would any other painting. However, while I was rendering the shapes and textures, I noticed I had to reconsider each of the metaphors in a more careful, personal, and embodied way than before: I had to remember how being on an open sea feels like and find out how composts work, for instance. This ultimately helped me to rewrite all the verbal components, page by page. First and foremost, I wanted to avoid explaining and keep the language quite concrete and evocative – so that the words would also show more than tell. Finally, once all the pages were done, I still decided to recreate the entire page 2, because its colour palette and lettering were too different from those of the other pages. One might consider such attention to aesthetics unnecessary when it comes to research publications, but personally, I believe constant reassessment and revision to be vital for all kinds of professional creativity, whether academic or artistic.

Overall, it is clear that my experience as a professional researcher and my experience as an amateur artist both shaped the process and the product in equal measures, and for the most part, I felt that these previously separate reserves of procedural knowledge complemented each other surprisingly well. There is no question that utilising the academic practice of analytical feedback helped to deepen and sharpen the ideas the comic aims to communicate, but the embodied, meditative process of painting also shaped both the script of the comic and my more general understanding of speculation. Overall, this new hybrid mode of creating was an eye-opening and successful metacognitive journey that I would happily take again.

Yet, the feeling remains that logic and revision always inevitably chip away at something – the rawness and fullness of the original vision – whereas the material and aesthetic flourishes distract from something else – perhaps some pseudo-Platonic idea of what I think I “actually” mean. After several hours of wordless painting, I would often find it difficult to pin down the conceptual structures I wanted to communicate, let alone to rephrase the textual elements. The argumentation, the writing, and the painting – while somehow converging in the same process – are such different modes of thinking that I could not immerse myself in them completely simultaneously. I usually needed to physically step away from the desk, take a break, and re-approach, if I wanted to think of the material I was working on in a different way – as concepts, as images, or as text. Thus, as the step-by-step breakdown of the process also suggests, bringing together different aims, modalities and skills in a complex creative project is something of a relay race, where one’s attention and working memory must be tuned to different levels and components alternately. In other words, bringing together artistic and academic creativity likely hinges on one’s ability to control one’s attention and cognitive resources – one must learn which mode to “switch on” at each juncture and how to do it.

References and Explanations (for Those Who Want Them)

All I can hope is that I juggled these modes well enough to create some sort of a balance between them. If not, there is a danger that the words and images do not communicate much, or conversely, that one or the other seems unnecessary for expressing the ideas discussed in the comic. Yet another challenge is presented by the fact that comics are something of a niche medium; some read them voraciously and others scarcely at all. So, in the following, I have compiled some additional page-by-page notes for those who might feel lost in the gutters. However, these are not meant to explain the entire comic away or contradict any other interpretations the reader might have. If these modest five pages inspire any new ideas in any readers at all, I have achieved what I set out to achieve.

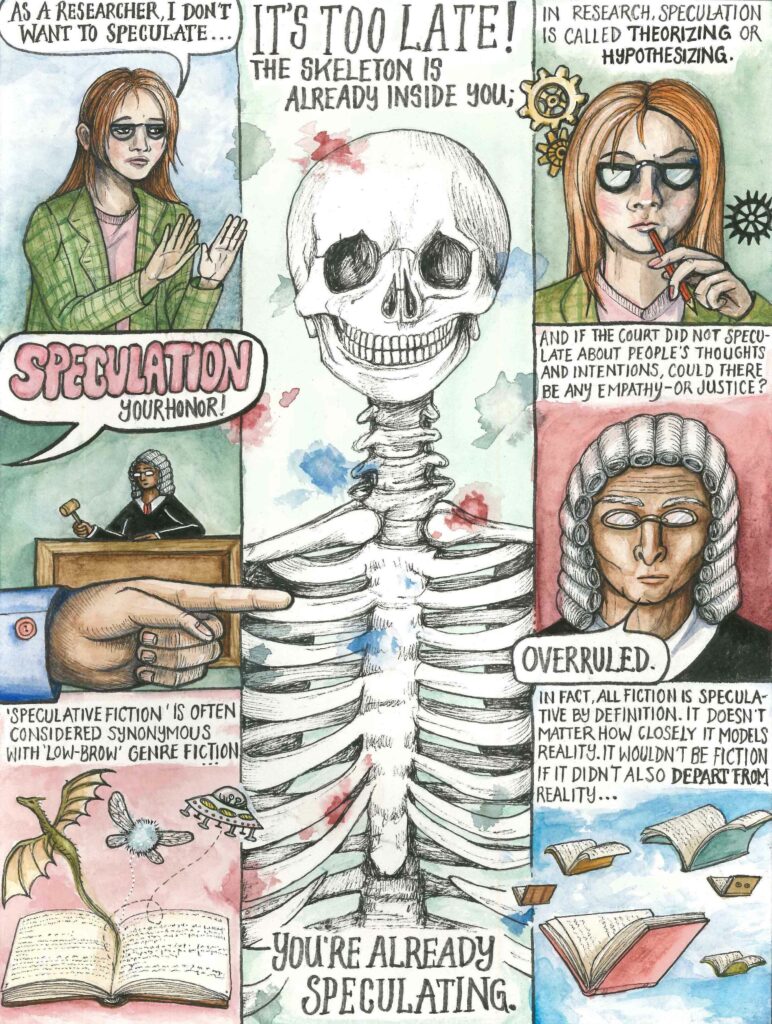

Page 1: The Skeleton

The first page nudges the reader to notice how much they already speculate, whether they like it or not. The word “speculation” has gained a negative ring in contemporary culture, because it is most often used to label instances where someone departs egregiously from facts, evidence, or consensus. In such cases, it can become almost synonymous with falsification, manipulation, or escapism. Yet, if speculation is defined as departure from certainty, it is necessary for our very survival.

We come face to face with uncertainty every day: the future eludes us, as do the minds of other people and creatures. Our knowledge, understanding, and perspective are limited. So, how could we possibly plan, dream, socialise, or empathise without employing some cognitive strategies for grappling with the unknown? Speculation could be construed as something of an umbrella term for such strategies, which include, for instance, the theory of mind or “mind-reading” (Zunshine), and science fiction’s large-scale speculations of the future (see Kraatila in this issue). All kinds of theories and forecasts, which are often accepted at face value, are also speculations in disguise (cf. Older in this issue). It does not matter how likely or unlikely, tangible or intangible the discussed possibilities are; as long as they are virtual, unrealised, or unverifiable, they belong to the purview of speculation – for the time being. After all, many of the uncertainties out there will turn into certainties sooner or later, and speculation can act as the scout or the vanguard that helps us to prepare for them.

A skeleton seemed like the perfect figure for guiding the reader through the comic because skeletons and all the speculations we must perform against all the uncertainty are unsettling for the same reason: they remind us of our own limits and mortality. Yet, as the “2spooky4me” internet meme jokingly points out, they have been inside us all along, completely inescapable. So, rather than trying to forget them, would it not be more beneficial to acknowledge and accept them? In the case of skeletons, this is usually accomplished by evoking the phrase “memento mori”, remember you are mortal. Perhaps a similar phrase should be linked to speculation as well, to keep us awake to our own imaginations?

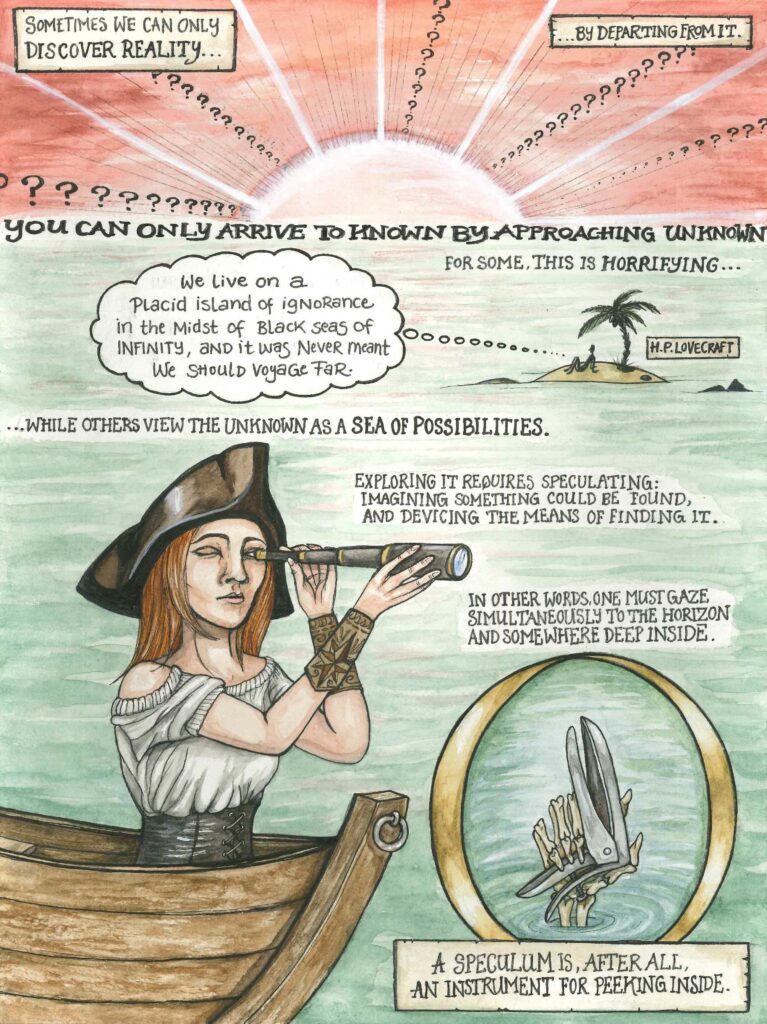

Page 2: The Sea

The second page stages uncertainty with the help of a familiar spatial metaphor: an uncharted sea, where weathers change unpredictably, and something is always hidden just behind the horizon. Describing imagination through the metaphor of a vast, mysterious space is extremely common among speculative fiction writers, possibly because it marries well with the kind of world-building that is central to the genre (see Kraatila and Bark Persson in this issue), or because it feeds into an embodied understanding of speculation as exploration. Margaret Atwood, for example, talks about going beyond the edges of maps, towards more unstable “cartographies” (67); Philip Pullman describes the “wild wood” of imagination, through which a writer must pick a path (89); and Emmi Itäranta explains she needs to “take distance” or “go to a different place” in order to get her imagination working properly (see Varis “Kuinka kirjailija spekuloi?” is this issue). The page also incorporates a rather famous quote from horror author H. P. Lovecraft’s short story “The Call of Cthulhu”. His stories, overall, continue the old maps’ “Here Be Dragons” tradition by populating the vast, unknowable depths of the ocean and outer space with unimaginable monsters. The edges of charted space thus approximate the edges of consciousness and imagination in speculative fiction.

Scientists and researchers, for their part, tend to approach the unknown more methodically, little by little. They usually manage their affordances – make invisible visible or extend their reach – with the help of various tools and instruments (cf. Varis “Strange Tools and Dark Materials”). This is represented by the boat, the spyglass, and the speculum, and contrasted by (the infamously racist) Lovecraft, who only sits on his island, unwilling to engage with his surroundings.

Page 3: The Compost

The third page concretises another group of metaphors that has been used to describe imagination almost as frequently as the uncharted spaces. Authors and researchers alike have repeatedly compared imagination to a natural phenomenon that lives and grows organically, transforming memories and experiences into something new, like a cocoon changes a caterpillar or a season a landscape. Neil Gaiman likens imagination to a garden (47) and myths to a compost (55); Ray Bradbury muses on a mysterious subconscious process that ferments his memories into fictions, which he in turn compares to dandelion wine (79–81); and Donna Haraway states no more or less than that “we are all compost” (161).

It has been generally believed, at least since Samuel Taylor Coleridge, that imagination must simply be a matter or recombining remembered ideas and experiences in new ways (ch. 13; cf. Lachman 121–122). Gaiman, likewise, quotes Lord Dunsany saying that “Bricks without straw are more easily made than imagination without memories” (54). Of course, on some level, we understand that this must also be how a compost works: it transforms scraps into rich, new soil by allowing their structures to break down and reassemble. But when this happens on minuscule, unseen, molecular scales, the process becomes so difficult to predict, record, or understand that it might as well be magic. Indeed, there are still many mechanisms and elements about the imagination itself that remain unexplored, uncertain, or unknown – and hence, a matter of speculation. This is why asking authors – professional speculators – to describe imagination may still be one of the best leads to understanding its functioning (see Varis “Kuinka kirjailija spekuloi?” in this issue).

Page 4: The Conspiracy

In contrast to the perceived naturalness of imagination, the speculations drawing from it – whether theories or works of fiction – are typically considered intentionally crafted, and thus, more artificial or less real. Indeed, defining speculation as a “cognitive or artistic strategy” implies that it can be used for altruistic as well as malicious ends, in moderation as well as in excess, in appropriate as well as in inappropriate contexts. Thus, the purpose of page 4 is to caution the reader of the potential risks and dangers of speculation.

As I have argued, speculation is a powerful, necessary component in creativity, and it can connect the fabulations of artists and the inquiries of researchers in various fruitful ways. However, if the lines between these domains are crossed blindly, uncritically, or with ill intent, the results can be more harmful than beneficial. That is to say, the cognitive procedures of speculation are so familiar from the valid scientific and philosophical theories that they might feel unduly convincing in the context of conspiracy theories as well. Conspiracies seem alluring partly because they offer alternatives to uncomfortable realities and convince the believers that by subscribing to such unpopular versions of the events, they are finally thinking for themselves – listening to their own reason. These illusions only make sense because creativity also requires connecting the dots and finding combinations that are not obvious to others, and academia also encourages the Socratic method of questioning everything. These are not inherently bad or wrong things to do, nor should speculation or its products be considered inherently suspicious. However, it is important to stay alert and aware of the limits and contexts of speculating, so that its products would not be mistaken for something that they are not.

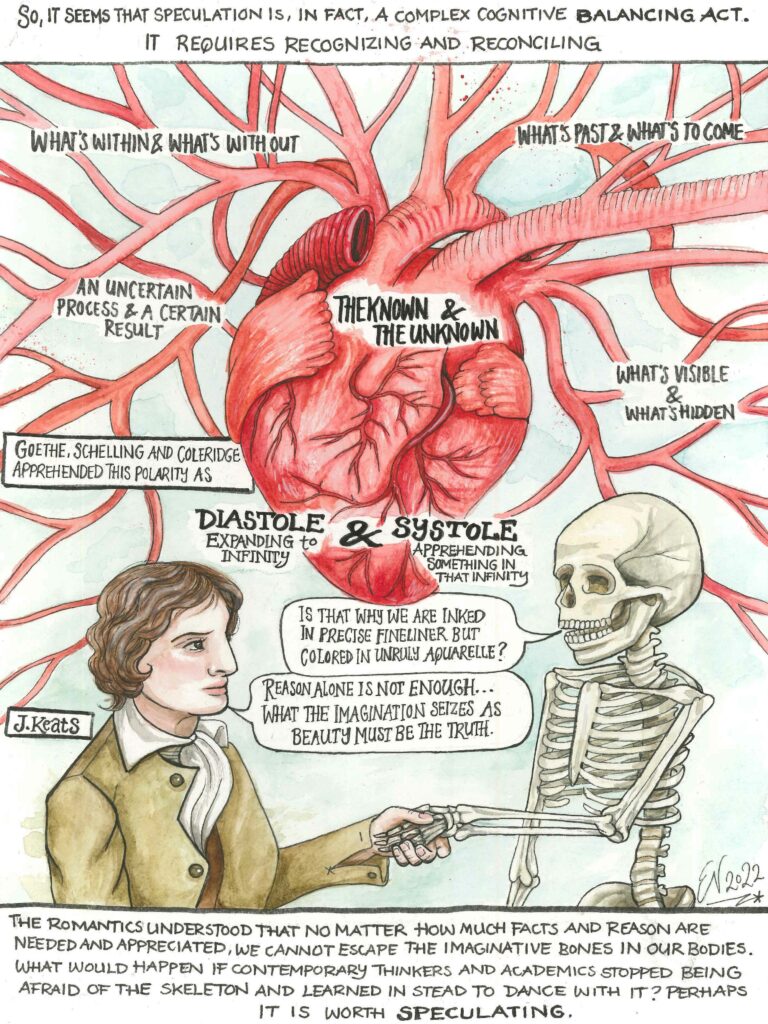

Page 5: The Heartbeat

So, how should researchers balance between reckless, uncritical speculation and the equally unhelpful rejection of speculation? The final page summarises some helpful suggestions offered by 19th-century poets and philosophers, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Friedrich von Schelling. These Romantic thinkers understood the relationship between knowledge and imagination quite differently from their positivist predecessors and contemporaries. The speech bubble attributed to Keats, for example, is a paraphrase from a letter he wrote to Benjamin Bailey on November 22, 1817. In it, the poet states that he has “never been able to perceive how any thing can be known for truth by consequitive reasoning [sic]” and that he is “certain of nothing but of the holiness of the Heart’s affections and the truth of Imagination”. “What the Imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth – whether it existed before or not – –” (Forman 68–69).

Most scientists living today would probably dismiss these thoughts as an overly sentimental opinion of a long-dead poet, but on the flip side, the aforementioned Romantic thinkers would equally lament a positivist, late-capitalist worldview where everything needs to be tangibly measured and valued in order to be acknowledged at all. At the same time, one thing that connects the Romantic poet and the positivist scientist is that they both must speculate. The difference is that the former is much more likely to be aware of it – and as I have already noted, awareness is the key ingredient that stabilises speculation, making it more beneficial than dangerous.

This is also reflected in the Romantic thinkers’ suggestion that, ideally, the search for truth and knowledge should employ both reason and imagination in turns, and in more or less equal measures. Schelling named these modes of thinking “contraction and expansion”, while Goethe used an even more overt cardiovascular metaphor and talked of “diastole and systole” (Lachman 79, 117). In other words, they believed that the kind of thinking that seeks to seize the universe with singular and immutable logics and definitions is just as dead as the kind of thinking that only interrogates and observes details and possibilities without ever establishing any hierarchies between them. Rather, in order to arrive at true understanding, one must flow or oscillate between these two tendencies, alternatively considering everything and grasping for something.6 My suggestion is that finding this heartbeat may become easier with the mindful utilisation of speculation and metaphor, their rational imagination and imaginative rationality. The skeleton is, after all, already inside you, listening and waiting for you to notice it.

If reading this comic led you to entirely different insights or you would like to see more of this type of content in Fafnir, we encourage you to send feedback to: submissions@finfar.org.

Biography: Essi Varis is currently working on her own postdoctoral project Metacognitive Magic Mirrors (2020–2025), which explores how different types of texts and images shape and expand speculative and imaginative thinking. The project is funded by the Finnish Cultural Foundation and carried out in the Universities of Helsinki, Oslo, and Jyväskylä. Varis specialises in 4E cognitive narratology, which she has previously applied, among other things, to comics and fictional characters. She is also one the reigning editors-in-chief of Fafnir.

Notes

1 This comic was made as a part of my postdoctoral research project, Metacognitive Magic Mirrors: How Texts and Images Enable and Extend Imagination (2020–2025). The project is funded by the Finnish Cultural Foundation and carried out in the Universities of Jyväskylä, Helsinki, and Oslo.

2 Although, as John Keats would maintain, these two may also be the same thing (Forman 68–69).

3 We arrived at this definition with my colleague Hanna-Riikka Roine following a concept workshop organised at the University of Oslo in May 2022. I would like to thank all the participants of the workshop for helping us refine our understanding of speculation.

4 For context, it should be noted that I have not received any professional training for visual arts, but have attended art classes for about 15 years as a hobby.

5 I would like to thank Karin Kukkonen, Merja Polvinen, Hanna-Riikka Roine, and the participants of The Northern Star symposium 2022 (October 17–18 in Nord University, Bodø) for all their helpful suggestions and encouraging comments. I hope you can see how big a difference your input made!

6 I have argued elsewhere that fantasy author Philip Pullman describes literary imagination and creativity as having similar polar phases or tendencies (Varis “Strange Tools and Dark Materials”).

Works Cited

Ahokoivu, Mari. Oksi. Asema Kustannus, 2018.

Atwood, Margaret. In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination. Doubleday, 2011.

Bradbury, Ray. Zen in the Art of Writing. Joshua Odell Editions, 1996.

Cave, Terence. Live Artefacts: Literature in a Cognitive Environment. Oxford UP, 2022.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Biographia Literaria. 1817. Edited by Tapio Riikonen and David Widger, Project Gutenberg, 2004, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6081/6081-h/6081-h.htm. Accessed 14 November 2022.

El Refaie, Elisabeth. “Comics Journalism.” Key Terms in Comics Studies, edited by Erin La Cour, Simon Grennan, and Rik Spanjers, Palgrave, 2022, pp. 65–66.

Farinella, Matteo and Hana Roš. Neurocomic. Norma Editorial, 2013.

Farinella, Matteo. The Senses. Nobrow, 2017.

Forman, H. Buxton. The Letters of John Keats. Cambridge UP, 2011.

Frith, Uta, Chris Frith, Alex Frith, and Daniel Locke. Two Heads: A Neuroscientists’ Exploration of How our Brains Work with Other Brains. Bloomsbury, 2022.

Gaiman, Neil. A View from the Cheap Seats. Selected Nonfiction. William Morrow, 2016.

Haraway, Donna. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6, 2015, pp. 159–65.

Lachman, Gary. The Lost Knowledge of the Imagination. Floris Books, 2017.

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. 1980. Chicago UP, 2003.

Leavy, Patricia. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice. Guilford Press, 2009.

Lovecraft, Howard Phillips. “The Call of Cthulhu”. 1926. The H.P. Lovecraft Archive, 2014, https://www.hplovecraft.com/writings/texts/fiction/cc.aspx. Accessed 8 January 2023.

Mazzuchelli, David. Asterios Polyp. Pantheon Books, 2009.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Harper Perennial, 1993.

Pullman, Philip. Daemon Voices: On Stories and Storytelling. Edited by Simon Mason. David Fickling Books, 2020.

Sousanis, Nick. The Unflattening. Harvard UP, 2015.

Varela, Francisco, J. , Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press 1991.

Varis, Essi. “Strange Tools and Dark Materials. Speculating Beyond the Limits of Narrative with Philosophical Instruments.” Limits of Narrative, special issue of Partial Answers vol. 20, no. 2, 2022, pp. 253–276.

Varis, Essi. Graphic Human Experiments: Frankensteinian Cognitive Logics of Characters in Vertigo Comics and Beyond, JYU Dissertations 77, University of Jyväskylä, 2019, http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-7725-2. Accessed 9 January 2023.

Zunshine, Lisa. The Secret Life of Literature. MIT Press, 2022.